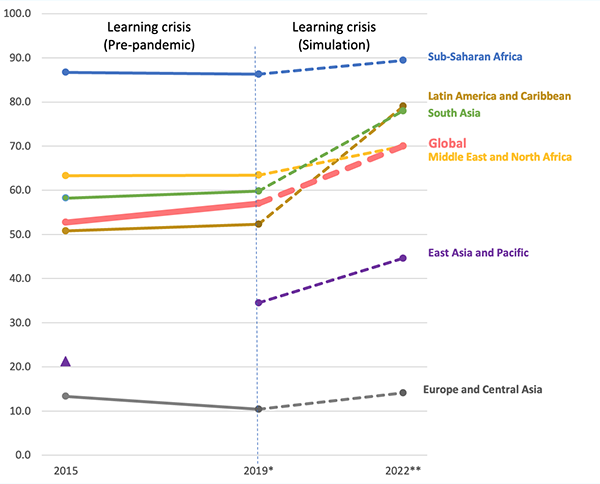

Education in the world is not going well. It was not going well before COVID-19 and it is not going well now. The learning poverty rate, which measures the proportion of children who cannot read and understand simple text at age 10, has increased substantially in recent years. This is confirmed by data from a report recently published by Unicef, Unesco and the World Bank together with other organisations, which show how this rate, which was already around 57% in low- and middle-income countries before the pandemic, has now reached 70%. The report also shows how global progress against learning poverty had already begun to increase in the years leading up to the pandemic, rising from 53% to 57% between 2015 and 2019, marking a reversal from the period between 2000 and 2015, when learning poverty fell from 61% to 53%.

Increases have been particularly large in South Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean, the regions where school closures, ineffective mitigation measures and household income disruptions have led to major impacts on the quality of education received by students, especially the most vulnerable. Thus, in the Latin America and Caribbean region, 80% of children of primary school age cannot understand a simple text, up from around 50% before the pandemic. The next largest increase was in South Asia, where projections indicate that 78% of children lack minimum literacy skills; the rate was 60% before the pandemic. In sub-Saharan Africa, increases in learning poverty were smaller, as school closures in this region generally lasted only a few months, but learning poverty is now at an extremely high level of 89%.

Learning poverty on a global and regional scale. Period 2015-2019 and estimates for 2022. Source: Unicef, Unesco and World Bank (2022).

70% of 10-year-olds are unable to read and understand simple text.

The importance of foundational skills

What do we mean when we talk about basic or core skills? They are the combination of skills, knowledge and attitudes, which all people need for their personal development, and to be active and integrated citizens in society. These skills are also the key that allows us to continue learning and to achieve more advanced competences (hence they are sometimes referred to as key or foundational competences).

Their determination and incorporation into school curricula depends on different school systems and countries. For example, the European Union recognises the following eight: linguistic communication, mathematics, knowledge of the physical world, social and citizenship, cultural and artistic, learning to learn, digital and personal autonomy and initiative.

High rates of learning poverty are an early sign that education systems are failing to ensure that children develop fundamental skills and are therefore far from achieving, and in many cases not on track to achieve, the SDG 4 target of universal quality education for all by 2030.

Learning poverty is also a serious threat to the future of an entire generation: if children do not acquire basic literacy skills – along with numeracy and other key competencies – it will be much more difficult for them to acquire the technical and higher-order skills needed to thrive in increasingly demanding labour markets, and for countries to develop the human capital necessary for sustained and inclusive economic growth. The loss of basic learning will result in lower skill levels, which in turn will reduce the productivity and income of today’s children once they enter the labour market.

If no action is taken, the current generation of students risks losing $21 billion in lifetime earnings in present value, or the equivalent of 16% of current global GDP. This economic cost falls disproportionately on low- and middle-income countries, where this generation of students could lose $11 billion in lifetime earnings.

If no action is taken, the current generation of students risks losing $21 billion in lifetime earnings

What can we do?

The good news is that policies are in place to make up for short-term learning losses, and that these policies will also enable countries to accelerate learning and overcome the crisis. The RAPID framework for the Recovery and Acceleration of Learning (recently formulated by UNESCO and the World Bank) synthesises the menu of policy interventions that countries could consider and adapt to their local context.

What is the RAPID framework? In short, the RAPID framework is a response that outlines five key policy measures that can be taken in the short term to make up for learning loss and put us back on track to achieve SDG 4. These measures are:

- Make the effort to reach all children and keep them in school. As schools reopen, it is crucial to monitor students’ enrolment, attendance and progress; to understand why some children have not returned to school; and to support them to return and stay in school.

- Implement regular assessment of learning levels. As children return to school, understanding their current learning levels, needs and contexts enables teachers, school leaders, system administrators and policy makers to make informed decisions about teaching approaches, assessment practices and other related policy measures to achieve learning recovery and improved outcomes. New forms of assessment should not only capture learners’ knowledge and skills, but also focus on helping them become more aware of how and what they learn. This includes promoting a culture of regular and inclusive assessment for learning by diversifying the types of assessment tools used, emphasising the use of formative assessments to meet individual learners’ needs, and leveraging technologies such as digital and hybrid assessments.

- Prioritise the teaching of key competences. Remedial learning efforts should focus on missing essential content and prioritise basic literacy and numeracy skills and knowledge, which students need to make progress in all subjects and to acquire more advanced skills in the future.

- Enhancing the effectiveness of teaching, including through accelerated learning. To enable rapid learning recovery, school systems must implement strategies that make education more effective, relevant and relational, and ensure that teachers can support the recovery process in the classroom. These practices include learner-centred remediation strategies such as structured pedagogical programmes, instruction targeted to students’ current learning levels, individualised self-study programmes, tutoring and remediation. Along with these strategies, extending instructional time by modifying the academic year or offering summer school can further accelerate learning recovery.

- Developing the health and psychosocial well-being of girls and boys. The pandemic has damaged the mental health and psychosocial well-being of both students and teachers, exacerbating the risks for those who are already marginalised. It is crucial to ensure that schools are safe and that children are healthy and protected from violence and can access basic services – such as nutrition, counselling, water, sanitation and hygiene. Promoting children’s well-being has great intrinsic value, and also has the benefit of promoting learning: children learn best when they experience joy and a sense of belonging at school.

We need everyone’s commitment

While these interventions can make a substantial difference in the short term, to achieve a broad and sustained acceleration of learning, they must be implemented on a large scale, and this implementation must be part of a long-term national strategy of structural reforms. Sustained progress on education indicators will depend on structural reforms that improve professionalisation and the status of teaching careers, provide well-designed teaching and learning materials, bridge the digital divide and ensure that schools are safe and inclusive spaces.

The recovery and acceleration of learning requires sustained political commitment at the national level, from the highest political levels to all members of society. To reverse the trend of the long-term learning crisis, national coalitions will be needed to promote learning recovery. These coalitions should include families, educators, civil society, the business community and all ministries (not just the Ministry of Education). Commitment must be translated into concrete action at national and sub-national levels, including better assessment of learning to address the huge data gaps, the setting of clear targets and progress, and the development of evidence-based plans for remedial and accelerated learning.

Only in this way can we achieve more effective, equitable and resilient education systems. Only in this way will we be able to make progress towards the goal of achieving quality education for all, guaranteeing children the future they deserve.

REFERENCES

Work Bank. (2022). The State of Global Poverty: 2022 Update.

Unesco, Unicef and the World Bank. (2022). From the recovery of learning to the transformation of education.