Dawn breaks in an ordinary Latin American city. In the Bolivian highlands, in a Brazilian favela, in the shadow of a Guatemalan volcano. In these schools, they don’t just teach letters or numbers. Often, these little schools are the glue upon which entire communities are built. At seven in the morning, when the first children pass through a gate rusted by time and underfunding, the headteacher has already spent an hour preparing breakfast. There is no secretary, no counsellor, no maintenance staff. There is her. And of course, there are them: a team of teachers doing the best they can with what little they have. And what they have, many times, is merely willpower.

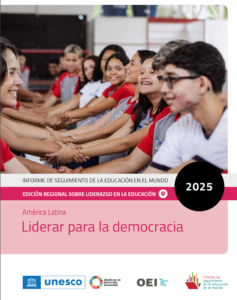

Who leads educational transformation in these contexts? Who keeps the school open when everything around is falling apart? The 2025 Regional GEM Report on Latin America and the Caribbean (Latin America: Leading for Democracy), published by UNESCO, shines a light on and defends the role of school leaders. It highlights their essential role in vulnerable environments and their place as agents of change where other powers have retreated. In the pages of this report, leadership moves from the margins to the centre. And in this article, we want to help give it the value it deserves.

What Educational Leadership Is and Why It Matters More Than It Seems

For years, talking about school leadership was, in many circles, just a fancy way of referring to inventory management: who signs the reports, how many chalks are left, whether the roof leaks. A bureaucratic view, inherited from top-down models, where the headteacher was little more than a key-wielding administrator. But that image is not only outdated—it is deeply unfair. True educational leadership has nothing to do with forms. It is about the future.

The report works to dismantle that misunderstanding. It offers a broad and realistic definition: school leadership encompasses pedagogical, community, ethical, and organisational dimensions. The leadership that matters—the one that transforms—is the one that drives quality teaching practices, builds support networks with families, defends inclusion, and nurtures relationships. In short, it is the leadership that turns a school into a space of possibility.

And there is data to back it up. The report shows that even in highly vulnerable contexts, strong leadership consistently contributes to better learning outcomes, lower dropout rates, and greater social cohesion. The pattern is clear: when school leaders are committed, supported, and empowered, educational gaps begin to close. There is no miracle—just daily effort guided by a vision that refuses to be defeated by scarcity.

Leading from Adversity

In the rural schools of Chocó, Colombia, when it rains (and it rains a lot), neither boats nor teachers arrive. But the school doesn’t close: the community leader acting as headteacher opens it anyway, organises classes with the local children, reuses materials, and improvises timetables. In the Andean highlands, headteachers walk several kilometres each week to visit students who tend livestock and can’t attend daily. On the outskirts of Lima, some teachers have turned their kitchens into digital classrooms so their students don’t disconnect from learning.

These are not exceptional cases. They are examples of the everyday leadership happening on the margins. Headteachers and teachers leading in adversity, where there are no support structures or stable resources. And yet—they build schools. How? By building community, caring for their teams, adapting minimal technologies, negotiating with authorities, and keeping the belief alive that learning matters—especially when everything else is falling apart.

We might call that silent educational innovation. It doesn’t appear at conferences or in academic journals. But it changes lives. With zero budget. No futuristic gadgets: born from necessity, contextual knowledge, and pedagogical creativity pushed to the limit.

The report recognises this kind of leadership as one of the invisible drivers of equity. But it also points to a structural problem: they are neither properly trained nor supported. Most of these leaders take on their roles without specific preparation, with little institutional backing, and with no space to share experiences. In many cases, they lead in solitude, carrying emotional and operational burdens that verge on the impossible.

Why does this happen? Because the system still sees leadership as a function of control, not a lever for transformation. Because in public policy, school leadership rarely has its own voice. And because major reforms—hungry for visibility—often forget the essential truth: that without trained, recognised, and supported leaders, no school can stand.

Training and Support: The Unpaid Debt to School Leaders

No one would hand a plane to an untrained pilot. No surgeon is given a scalpel without years of supervised practice. Yet in much of Latin America, school headteachers are handed the helm of entire educational communities with no specific training, no mentorship, no support network. They are asked to lead without being prepared to do so—and often under adverse conditions.

The report confirms it: educational leadership training is weak, fragmented, and in many cases, non-existent. In some countries, access to leadership training depends on isolated initiatives, often external to the system, with no continuity or integration into public policy. Administrative control is prioritised over pedagogical or community development. As though leading a school were just paperwork.

But as the best examples show, leading a school means supporting teachers, resolving conflicts, translating national policies into local realities, managing scarcity without losing hope. It requires pedagogical, emotional, and political skills. And above all, it requires not being alone.

That is why the report insists on a key word: support. It’s not enough to offer the occasional course. Professional development paths must be created, peer dialogue spaces enabled, and collaborative networks established to break isolation. We must understand that leadership is neither innate nor magical—it is a capacity cultivated, learned, and strengthened over time with the right support.

The report also highlights a lack of systematic data: many countries don’t collect information on who leads schools, how they are trained, or what results they achieve. This statistical invisibility reinforces political invisibility. What is not measured is not managed. And what is not managed leaves leadership to chance.

Focusing Where It Matters: Leadership, Policy, and Equity

The education agenda in Latin America often speaks of inclusion, quality, and transformation. Big words. Necessary ones. But often disconnected from the real conditions in which schools operate. Between technical discourse and daily practice lies a bridge that is seldom crossed: school leadership. As the report says: if education systems want to move towards equity, they must focus on what truly matters.

School leadership can no longer be a minor appendix to education reform. It is a structural factor. Yet in many countries, regulatory frameworks still lack robust policies for the professional development of school leaders. Only a handful of systems have clear pathways for access, continuous training, and institutional support for leadership roles. In some cases, leadership is assigned by rotation or seniority, with no pedagogical criteria or support strategies.

The report also highlights a lack of systematic data: many countries don’t collect information on who leads schools, how they are trained, or what results they achieve. This statistical invisibility reinforces political invisibility. What is not measured is not managed. And what is not managed leaves leadership to chance.

The good news is that there are (tentative) signs of change. In recent years, some countries have begun to rethink the role of school leadership in public policy. Pilot mentoring programmes between headteachers have been launched, competency frameworks developed, even collaborative networks created. It’s not enough—but it shows that leadership can move from a solitary figure to a systemic force.

Focusing on leadership doesn’t mean ignoring other variables—it means understanding that all education policy becomes real (or fails) in the microspace of a school. And that in that space, leadership makes the difference. If educational equity is a shared goal, then training, supporting, and empowering those who lead schools must stop being a footnote. It must be at the centre.

What Now?

For too long, school leadership in Latin America and the Caribbean has been a secondary issue. Invisible in the data, neglected by policy, and sustained—almost always—by the personal commitment of those who understand that educating is more than teaching. The report sends a clear warning: without a determined effort to train, support, and empower school leaders, equity will remain a distant goal.

What must be done now is to turn diagnosis into action. That means reviewing regulatory frameworks, investing in contextualised training, establishing clear professional pathways, and above all, recognising leadership for what it is: a key piece in the educational machinery.

It also requires a change in perspective. We must stop thinking of leadership as an administrative or charismatic role and start seeing it as a collective, situated capacity capable of mobilising entire communities.

The challenge is great. But we are not starting from zero. In hundreds of schools across the region, those leaders already exist. What’s lacking is not willpower—it’s public policy that supports them.