A Critical and Thoughtful Reflection

We need to open a reflective dialogue about our responses to socio-educational challenges. A thoughtful reading in which we discard equivalences that are becoming increasingly universal in our interventions and causing confusion.

Una

One of these is equating dispersed activism with the multidimensional approach required by any socio-educational intervention. If we add increasingly rushed implementation times, disguised as efficiency, it is easy to lose focus and, consequently, impact. Moreover, if we wrap this modus operandi in the tsunami of immediate communication we live in, instead of contributing to collective intelligence, we are doomed to a “desert of noise,” leading us to assume unverified narratives based on beliefs that create mirages in our action plans, which fade away at the slightest evaluation.

We need to open a joint dialogue that makes us question the myths that often guide our intervention, understanding these as the narratives and beliefs that shape our way of perceiving socio-educational reality and, therefore, our actions upon it.

The questions I present here for this collective reflection stem from a main myth: a successfully proven innovation can be scaled up, optimising resources, training educators, and disseminating it effectively. They emanate from a self-critical exercise in the planning of educational projects in Latin America and Spain in which I have participated over the past two decades.

de ellas es equiparar el activismo disperso al enfoque multidimensional que toda intervención socioeducativa requiere. Si a esto le sumamos los tiempos de implementación cada vez más precipitados, camuflados de eficiencia, es fácil perder el foco y, por ende, el impacto. Y, si además, envolvemos este modus operandi en el tsunami de comunicación inmediata que vivimos, lejos de contribuir a la inteligencia colectiva, estamos abocados a un “desierto de ruido”, que nos conduce a asumir relatos no contrastados, basados en creencias que generan espejismos en nuestros planes de actuación y que se desvanecen ante la mínima evaluación.

We need to open a joint dialogue that makes us question the myths that often guide our intervention

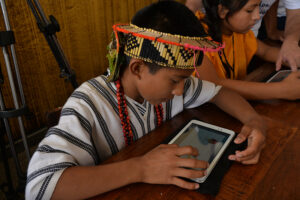

Myth 1: The success of a socio-educational innovation is universal

Although educational challenges and methodological solutions have a universal character, practice has shown us that it is not always easy to transfer an innovation to other socio-cultural contexts. Why does this happen? The success of an innovation does not depend on its excellence or methodological nature but on the socio-educational community’s capacity to embrace it, incorporate it into its own system, and implement it sustainably. Not every innovation is for everyone at any time. We must very precisely identify the requirements that must be met for an innovation to take root in a socio-educational community. If these requirements are not met, the first thing we need to consider is helping to create the appropriate conditions for that innovation to take root, grow, and develop fully and creatively.

How can this challenge be addressed? By not underestimating either the methodology or the time needed to analyse the needs and conditions of an educational community. It is in this initial diagnosis (which should be participatory) where what we call evidence-based intervention begins. This analysis must ask if, with the innovation we propose, we are addressing the problem identified by the community from which we build the entire theory of change. In this analysis, we must identify the barriers that prevent the community from embracing this change. We must also assess the convergence of factors that might at any given moment cause an innovation to fail in a particular context.

Myth 2: Training trainers is sufficient for transfer

Another mantra frequently repeated in socio-educational intervention is that the transfer of an intervention is fundamentally based on training trainers. However, practice has shown us that scaling through training alone is insufficient and does not guarantee success. In these cases, the so-called modelling is the factor that makes the difference. Modelling, which involves documenting and standardising each process of an intervention, as well as providing tools that enable teaching and learning processes, is essential to ensure its quality and adaptability. It provides a clear framework for implementation, preventing the innovation from becoming diluted or turning into something unrecognisable. Why is it so important? Because training trainers without modelling cannot guarantee the transfer of an educational innovation when the turnover rate of trained personnel reaches nearly 75% in some educational centres. This modelling provides a clear framework for implementation, facilitating the personalisation of the innovation without compromising its integrity.

Myth 3: Scaling at zero or minimal cost

One of the most persistent myths in the field of socio-educational intervention is the belief that scaling an intervention always leads to cost reduction through economies of scale. This idea, although theoretically attractive, does not always hold in practice. Experience shows us that there are unavoidable costs that cannot be optimised simply by increasing the scale of the intervention and, in some cases, attempts to reduce costs may even compromise the project’s effectiveness and sustainability.

First, it is crucial to understand that any innovation or intervention brings about change, and every change must be managed. Change management is not cost-free. Implementing an intervention on a larger scale involves a series of adjustments and adaptations that require significant resources. For example, the modernisation of processes, the training of new teams, and the adaptation of materials and methodologies to different cultural and educational contexts are all activities that require a considerable investment of time and money.

In conclusion, how can we help transfer efficient responses to universal socio-educational challenges? The more focused the purpose of our intervention, the more we will support the educational community in identifying its priority agenda. Precisely because both educational action and vulnerability are multidimensional and changing, and our operational capacity has a limited time and financial framework, we must help the community optimise its energy and creativity in addressing the priority focus from its own theory of change.

In any case, to turn our intervention myths into decisions informed by participatory action research, we need time, mechanisms, and accomplices so that socio-educational reality can challenge us.