“Awareness of the development of digital skills is no longer an ancillary matter in Latin America and the Caribbean. It has to be a core issue. The pandemic has made this very clear, urging us to work fast, intensify our efforts and bring in civil society. We can’t have a generation affected by a process that’s left learning unevenly distributed by factors such as income and internet connection disparity”. This declaration of intent made by Colombian Minister of Education María Victoria Angulo in conversation with Magdalena Brier, ProFuturo’s Managing Director, contains some of the key elements of the Latin American country’s strategy to move its education system forward at the pace required by the fourth industrial revolution and the major changes that the latter has brought about in our society. These include developing digital skills and learnings for the future, bridging divides and collective endeavour.

We know from the experiences of other countries that technology can have a significant impact on education. For example, it can reduce learning gaps, enhance teachers’ career development, improve the efficiency of day-to-day management and generate and process information to improve lessons and even education policies (Mateo and Lee, 2020). However, for technology to achieve all the above for education, it must form part of comprehensive and more ambitious reforms, with many other elements at play. For example, a vision that’s unique to each country and shared by all the actors in the system, which also puts equity and inclusion at the heart of the strategy (Mateo and Lee, 2020).

Innovation, yes. But innovation with a purpose. In this article, we’ll discuss the educational innovation ecosystem that’s being implemented in Colombia, together with its main axes and the programmes by means of which it’s taking shape.

RECONNECTING TO EDUCATION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, 165 million students in LAC were “switched off” from education (IDB, 2020). In Colombia the figure reached almost 10 million. In view of this situation, teachers, families and governments made strenuous efforts to maintain the levels of learning, with websites and platforms with educational resources, online classes, radio and TV lessons and text messages to send homework.

However, despite these efforts, the data indicate that a large number of students have remained disengaged from learning activities, most of them have spent half as many hours studying and, even more seriously, many of them will be permanently disconnected from education and they won’t enrol again. This was because until COVID-19 came into our lives, the presence of technology in education had been of a merely token nature, with very few exceptions.

But the fact is that, with or without COVID-19, education systems must move forward to cope with the massive changes that have been transforming our lives for a number of years. This is a reality throughout the world, but it’s even more evident in the Latin American and Caribbean region, where there are serious inequalities in access to education for a large part of the population and where the standstill in learning and the risk of dropping out of school are jeopardising the progress achieved in terms of access over the last two decades.

THE MAJOR CHALLENGES ON THE EDUCATIONAL AGENDA

With the above in mind, what are the major challenges that a national educational innovation strategy should address? How should they be addressed?

Education gaps, enhancing learning and the culture of connectivity

As a result of the existing inequalities and connectivity gaps, the pandemic has widened the differences between the most advantaged and the most vulnerable students. The efforts to close these gaps must therefore be redoubled. In the words of María Victoria Angulo, “the use of technology at schools can help to bridge the digital gap, but also the cognitive divide”. To do so, the first step is to make progress in terms of connectivity. In Colombia, according to an ECLAC report, only 67% of 15-year-old students have an internet connection, only 62% have access to a computer and only 29% use any educational software. Moreover, according to the data of the Ministry of Education and the Icfes analysed by the LEE (Laboratory of Economics of Education) at the Javierian University, only 17% of rural Colombian students have a computer and internet.

In the Colombian strategy, connectivity is regarded not only as the physical ability to be connected to technology but also in a much broader sense. Thus, it talks of a “culture of connectivity” which, in the Minister’s words, means “preparing all the communities to understand all the potential that connectivity provides them with. What it means to be connected”.

For this purpose, the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, in partnership with that of Education, is furthering a rural connectivity project that is expected to reach more than 14,000 connected schools over the next 10 years.

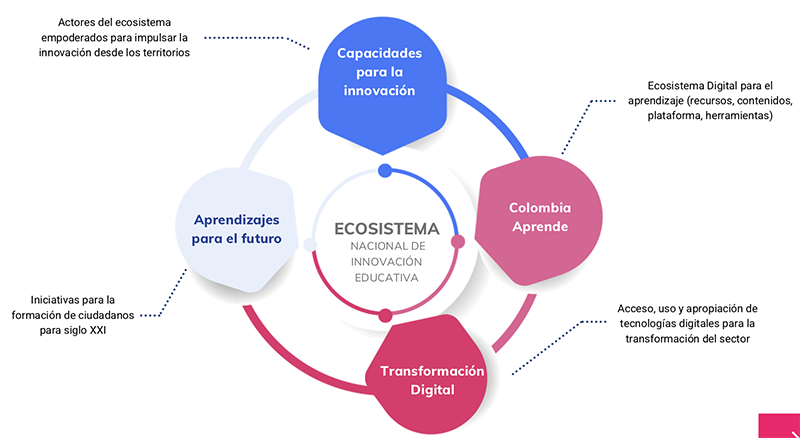

The country has also developed a national educational innovation ecosystem made up of programmes such as Colombia Aprende, a set of educational platforms with more than four million users that’s available to teachers and students who, through it, can access all kinds of resources, guides, guidelines, MOOC-type courses and a joint working platform for teachers, and Aprendizajes para el futuro, a series of initiatives for the training of citizens for the 21st century, by means of which children can learn to programme (coding for kids), become familiar with science, maths, engineering and technology contents (the STEM+ approach, the 4th Industrial Revolution and EdukLabs) and become involved in actions designed to promote safe and reliable digital environments.

Teaching skills

According to the above-mentioned Javierian University study, 48% of the country’s state school heads believe that their teachers don’t have the technical and pedagogical skills required to integrate digital devices into their teaching. In this regard, as the Minister of Education states, “we need teachers who incorporate technology into their work. We’ve created a programme called Contacto maestro that’s not only about technology connecting us, but also about connecting us with empathy”. Thus, Contacto Maestro is a platform for teachers with information and resources to enable them to train, connect with other teachers and care for themselves. They’ll find a wide range of training opportunities, calls for research and knowledge promotion, networks, mentoring and communities of practice; they’ll thus be able to “do their magic better”, motivating their students and making their classes more fun and enjoyable by means of new media.

Evaluar para Avanzar

Assessing the current status of all the elements in the education system is essential for identifying what we need and how to move forward. For this reason, Colombia has just launched Evaluar para Avanzar, a national strategy to improve the quality of learning by means of an evaluation process whose results should serve as a basis for generating innovative curricular proposals and accompaniment strategies with a positive impact on the students’ progress. In addition to the student evaluations, this public policy envisages skill enhancement for all the actors involved in the educational process (including the families), the analysis, interpretation and appropriation of the evaluation results and the development of academic and pedagogical reinforcement plans based on these results.

THE CLUES TO THE COLOMBIAN CASE

Colombian students have just returned to the classroom after the hiatus caused by the pandemic and it’s too early to assess the results of the national strategy, which has also been significantly affected by the health crisis. However, this strategy can offer us some clues as to what characteristics a public policy that seeks to successfully integrate technology and innovation into a country’s education system should have:

- A vision or purpose: at the basis of any education strategy there must be a clear vision stemming from the specific context of each country, one that’s shared and agreed upon by each and every one of the players in the education system.

- Equity and inclusion as key principles: if equity and inclusion aren’t at the core of the strategy, technology will increase the access and learning gaps.

- Investment in connectivity and infrastructures: As a result of the above, the digital gap needs to be bridged by expanding connectivity and the possibility of access to digital devices to all parts of the country, paying particular attention to the most vulnerable students so as to level the playing field.

- Training in digital skills: digital competences and the 2030 skills must be included in school curricula to enable students to acquire the knowledge they need to become the citizens that the new society is demanding.

- Teacher training and empowerment: teachers must understand, share and take ownership of their new roles as mediators, analysts, facilitators and designers of new learning experiences. For the above to occur, public policies must understand the vital role played by teachers in the new form of education and provide them with training and career development opportunities.

- Assessment: Technology makes it easier for us to gather and analyse data to constantly evaluate and monitor how the system is operating. To find out where we are and what we need to get to where we want to be.

- Public-private partnerships: partnerships with private actors are highly useful for reaching places the public can’t get to. Leveraging the experience, knowledge and portfolio of products that are proven in the private sector can amplify the effects of the public policies.

According to Minister Angulo, “Latin America can’t lose the momentum of recent years, during which education has become a major issue on the agenda.” The pandemic has put education at the centre of the debate and the global political agenda. We must build on this momentum to curb the inertia that’s made the region’s education systems some of the most unequal and inefficient ones in the world.