As we have already reported in this Observatory, the advances in technology and data science in recent years offer great possibilities for education. Today, with development of information technologies, personalisation of learning, an educational approach that was born almost with Socrates, has taken a new evolutionary leap: intelligent tutoring systems, free access to numerous learning platforms, methods that use computers to adapt the complexity of content to the user’s needs…

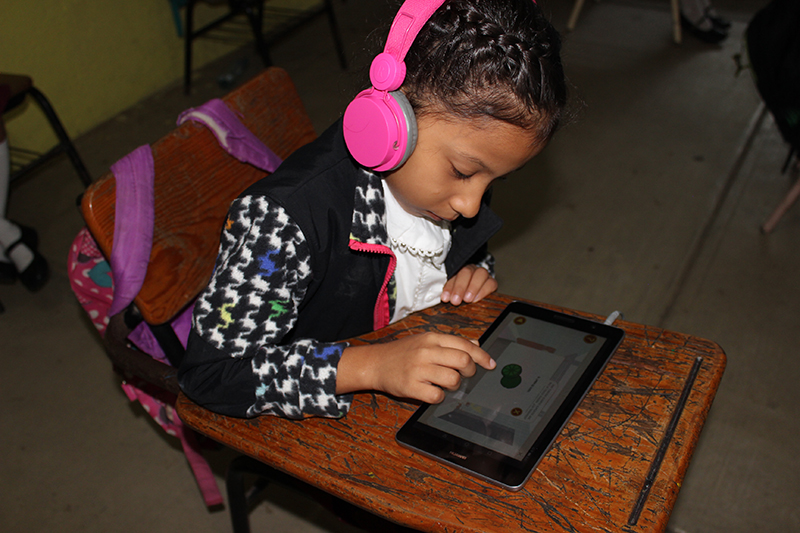

The adaptive nature of personalised digital learning to “teach at the right level” makes it particularly useful for bridging educational gaps in the most vulnerable environments. However, evidence on their effectiveness is still lacking and research on key factors such as design, implementation and scalability remains scarce.

To address this lack of information, UNICEF’s Office of Global Insight and Policy (OGIP), with support from the Office of Research-Innocenti embarked on a landscape review to take stock of digital personalised learning solutions in low- and middle-income countries. The study has identified more than 1,000 products from which 40 have been selected for analysis. What were the main findings of this report? What lessons and recommendations can we draw from this analysis? We’ll see below.

The adaptive nature of personalised digital learning to ‘teach to the right level’ makes it particularly useful for bridging educational gaps in the most vulnerable environments.

Coverage: local innovation and flexibility of use

Knowing where these products are deployed and in what kind of contexts is key to understanding their potential and identifying market gaps. In this regard, UNICEF’s analysis highlights the following findings:

Personalised digital learning is used in these settings but with uneven penetration. Personalised learning products are used in different settings in low- and middle-income countries. Most of the products analysed are developed locally, but their market penetration remains uneven and varies by country and scale. For example, China, India and Brazil have the most active market and penetration is weakest in the French-speaking countries of Central and West Africa. In terms of scale, some products have more than one million users and others have less than 100,000.

The seed of local innovation is planted. Local innovation and entrepreneurship drive the growth of personalised education in vulnerable environments, with 27 of the 40 products based in a low- or middle-income country. However, products based in high-income countries have, on average, a larger footprint in terms of middle- and low-income countries covered.

Too much focus on Mathematics and Literacy. About half (21 out of 40 products) are concentrated in one or two subjects, with Mathematics and Language/Literacy being the two most common. Evaluations have focused disproportionately on learning outcomes in Mathematics and Language/Literacy, while the evidence base on the effectiveness of learning programmes in other subjects and skills is weak.

Local languages but only the dominant ones. More than three quarters of the participatory learning products examined are available in at least one local or regional language. However, products deployed in South and South-East Asia tend to offer a greater variety of local languages compared to products deployed in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Flexible use. Personalised learning products are used flexibly in a variety of educational contexts, although they tend to be used primarily for supplementary learning, either at home or at school. However, there have been very few comprehensive evaluations comparing the different models in terms of their success, effectiveness and impact criteria.

Content and pedagogy: on the right track with room for improvement

The aim of analysing content and pedagogy is to identify unmet gaps and highlight best practices that will enable a more effective role in supporting student learning. The following are the main findings of the report:

Adapted to the local culture and context. Personalised learning products offer multiple types of content, most of which are adapted to the local culture and curriculum of at least some countries of deployment. The most frequent contents are practical exercises, evaluations and games. However, the depth of curriculum alignment varies.

AI for personalisation. The personalised learning solutions analysed use different methods to tailor learning pathways to the educational needs of learners. 60% of personalised learning products use Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based learning pathways, although there are many variations depending on the technology and algorithms used. There are also differences based on which aspects of students’ learning are adaptive (review, practice, feedback, assessment, sequencing…).

Student motivation. All of the solutions reviewed offer some features to encourage learner engagement, although these features are very basic and little is known about their effectiveness and how they can best be harnessed to influence learning behaviours and outcomes in e-learning environments.

The teacher only supervises. 85% of the products reviewed incorporate a teacher function, but this is often limited to monitoring and less than a third provide prompts or incentives for teachers to take action related to their students’ learning or to communicate with other educators or parents.

Outcome data do not translate into practical recommendations. The information shared with students about their performance/progress varies. Most of the dashboards reviewed (26 out of 40) provide data on current performance. Half of the outputs share results broken down by skills, while 17 outputs provide feedback to the learner on their distance from the intended learning objective. Most of them share student performance data with teachers through teacher portals, but less than half do so with parents and school leaders. However, even when student performance results are made available to teachers, parents and/or school principals, only a few products translate these data into practical recommendations or follow-up interventions.

Design and technology: some limitations

Identifying promising approaches and gaps in design and technologies could be the basis for identifying elements that are crucial for product acceptance and effectiveness. In this regard, what have UNICEF’s findings been?

Only 40% offer offline access. Although several products have taken some steps to mitigate connectivity limitations, significant gaps remain. For example, about half are accessible via multiple devices (laptops, desktops, smartphones and tablets), but only three are accessible via landline phones. Less than half (16) offer some form of offline access. Offline functions vary and include access to learning content, practice exercises and/or feedback. However, only a few products incorporate access to multiple offline functions.

Complex registration and start-up requirements. Personalised learning solutions offer several features for ease of use and navigation, but registration and login requirements can be cumbersome. Although all the solutions analysed offer some form of facility to simplify use and navigation, almost none of them offer simple registration mechanisms to reduce barriers to accessing the platform.

Data protection gaps. Although providers of these solutions protect users’ personal data in various ways (data encryption, anonymisation, third party sharing controls, data security policies, etc.), these measures are not widely adopted.

Inclusiveness: still a long way to go

The analysis of this aspect aims to identify underserved user groups and to find out which aspects of design and implementation need a more inclusive approach. These are the findings of the analysis.

There are still excluded pupils. PL products target various population groups, but some categories of learners who are already highly disadvantaged remain underserved. These include pupils with disabilities, out-of-school children, ethnic minorities, displaced children, etc. Thus, only 22.5% of them are addressed to out-of-school students, 12.5% to displaced children and 7.5% to ethnic minorities.

Limited sustainability and scalability

This analysis helps us to understand some key factors for the scalability and future sustainability of digital personalised learning solutions, such as the degree of involvement of local stakeholders, the type of business model and the measurement of results.

Government involvement is weak. Expanding and sustaining educational technology requires much more than enthusiastic students and motivated educators. It requires the alignment of multiple stakeholders in local ecosystems, including government, education innovators, funders, etc. In this regard, the study has found that local stakeholders are often involved in content development, but less so during implementation, and government involvement is low throughout the process.

Few products have established a self-sustaining business model that ensures their survival and prosperity and minimises or eliminates the cost to students and their families.

Few open principles. Only 17.5% of the solutions analysed have adopted open principles, i.e. they have made their content and/or technology freely available.

No product evaluations. Most of the solutions analysed have some form of impact assessment, but these are often not publicly available (less than half) and it is difficult to compare the effectiveness of the products.

These findings and lessons learned yield a large number of recommendations and actions to be taken that could make digital personalised learning realise its full potential to help close learning gaps in the most vulnerable contexts. These recommendations will be discussed in a future article.