We have learned the theoretical foundations of personalised learning, three different approaches that get down to specifics and explore how technology can help to take learning to another level. In this post we will explore the three proposals that bring flipped learning, challenge-based learning, and place-based learning into the classroom.

HISTORY IN REVERSE: FLIPPED LEARNING, SQUARED

How do we connect history to the reality of our students? How can we bring events far away in time and space closer to them and turn history into something close to them, that speaks to them and have them understand the world they live in? These were the concerns of Manuel Jesús Fernández Naranjo a secondary school social sciences teacher in Spain. A great believer in the power of active teaching methodologies, Manuel Jesús was already using flipped learning in his history classes. But he wanted more. He wanted his students to create that connection with their immediate reality. He wanted history to be “something that helps them understand themselves and has really happened to real people like them”.

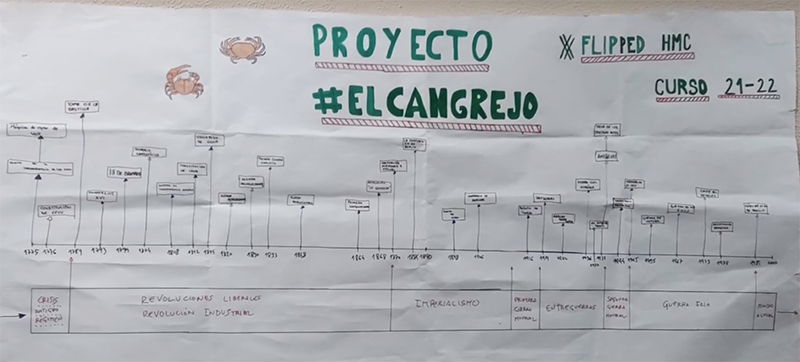

This is the origin of the project El Cangrejo: agency of historians. “The idea is to focus on their concerns about current affairs and go back in time to explain their root causes, and thus have a much better understanding of a number of current issues, such as the resurgence of fascism, why some countries live in poverty today, or why there is a Catalan independence movement.

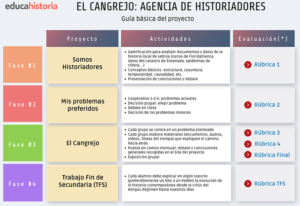

The project, which Manuel Jesús and his students developed as they went along, consists of four stages, which are explained in this video from the website educahistoria and which we summarise below:

- We are historians: At this stage we start small and proximate. Gamification is used to analyse data and documents from local history, that of the municipality where the students live and grow up. In this way, they learn basic concepts in history such as conjuncture, structure, temporality and causality, which are very important tools for working in history. Once the research has been completed, a final discussion is held to draw conclusions about what we know about our municipality.

- My favourite problems: in this phase, there is group work to analyse some current issues, no longer local but general in nature. Each group chooses an issue and explains to the class why it exists and why they are interested in it.

- El Cangrejo, the agency of historians. Of the issues that emerged in the previous phase, each group focuses on one issue raised and begins to delve deeper. Each group has to develop materials (documents, audios, videos, timelines…) explaining the way back. They have to analyse the origin of the issue, why it has become what it is today, whether it has always been like this… At the end, a debate and a sharing session is held to present what they have found out about the issued they have had to investigate.

- End-of-Secondary Final Project (EFP). At this stage, the students use what they have learned to move on to the more general picture. In particular, they are asked to use the methodology they have already used to interpret a broader, more generic historical period. Specifically, contemporary history. From the crisis of the ancient regime to the present day, they must be able to analyse and interpret large periods of time and their major issues. This stage is individual and the support used by the students is preferably digital (a website or a padlet).

For this project, Manuel José adapted the more traditional flipped methodology: “I realised that we could do it the other way around, i.e. watch the videos of the topics from the end to the beginning to follow the approach of the El Cangrejo project and in that way, with my support of what they need from previous topics, continue to progress with the research on the causes of the issues they are dealing with. And that’s where we are.”

A flipped learning experience that, in addition to turning history upside down, takes the concept of active learning to the limit: the Cangrejo Project was conceived by a teacher, but the students have played a major role in the development of the proposal. It also uses other methodologies and approaches such as cooperative learning or gamification, and works transversally with different digital environments and tools, meaning students can also develop their digital skills.

CHALLENGE-BASED LEARNING: THE CLUB 2030

The children in the 2030 Club will travel to Mauritius to carry out a Peace and Community Mission that will help them to save the planet. On their trip, they’ll learn many interesting things about Mauritius, but also about the Sustainable Development Goals set by the United Nations to ensure that all countries embark on a new path to improve the lives of everyone without leaving anybody behind. Specifically, goals number 16 (to promote just, peaceful and inclusive societies) and 17 (to revitalise the global alliance for sustainable development or, for children, work as a team). They’ll also travel to Norway to develop the Humanity Mission. To carry out this mission, they’ll have to understand SDG numbers 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5: end poverty, end hunger, lead a healthy life, receive a better education and achieve gender equality. There are many more countries and missions. And, above all, many things to be learnt through play. We’re referring to the 2030 Club, an initiative that’s arisen from the partnership between Education for Sharing and the ProFuturo Foundation.

The 2030 Club is a training proposal that seeks to go beyond the mere dissemination of information on the global challenges. The Club aims to trigger the participation of both teachers and students. To empower them and turn them into agents of change so that their actions go further and become tangible projects that benefit their communities. Like all ProFuturo’s educational proposals, the 2030 Club includes a teacher training proposal to enable teachers to take it to their classrooms and make the most of the programme.

The didactic proposal of the 2030 Club includes mandatory and optional activities. The pathway is divided into four missions: Humanity, Progress, Environment and Peace and Community, as well as an introductory training session during which the children will learn the basics of the SDGs.

- To begin the work with each of the missions, an imaginary teacher-guided journey will be embarked on with the help of a previously structured script or the support of a digital resource that will bring the students closer to the context of the place visited. The aim of this initial activity, which is mandatory, is to provide the students with relevant information on a country, such as the social, geographical and cultural aspects and its initiatives and challenges related to the SDGs that will be addressed during the mission.

- The following activity, also mandatory, is a recreational exercise designed to detonate the students’ previous knowledge and contextualise the following activity.

- The third stage is a digital activity that enables the students to initiate an action to contribute to the goal they’ve studied.

- Once the activity has been completed, the teacher will assign a closure space to encourage the pooling of educational experiences and reflections related to them.

The result is a learning club suited to us all, membership of which will give us access to a very special way of seeing the world, namely that of critical and conscious citizens who are respectful towards their environment.

PLACE-BASED LEARNING OR WHEN NATURE IS SCHOOL

Picture: RTVE.

First, that old nostalgia: Who doesn’t remember the feeling of absolute joy when the teacher announced that the class would be held outdoors that day? And then comes the fact: today’s children spend less time outdoors than prisoners. Specifically, half the time.

This study was funded by a detergent brand. Although bizarre, it makes sense and obeys a basic premise of the Forest School philosophy: if children don’t go home dirty and muddy, they haven’t played enough. Another of its premises follows the same logic and comes to us by way of this video from Jean Lomino, founder of the Forest School Institute for teachers: “I think I would be very worried if I walked into a classroom and saw all the children sitting at their desks writing non-stop. That would be a big problem because children should not be sitting and writing but standing up and experimenting.”

What are Forest Schools? An outdoor culture-based learning style where pupils can learn through a long-term process involving play, exploration and support for risk-taking, so that they can develop personal confidence and build self-esteem while living in a natural environment (UK Forest Schools Association).

This approach helps students to develop socially and emotionally through, above all, a holistic understanding of risk. In Forest Schools, risk is in everything we do and we grow when we overcome them. Taking risks and making mistakes is a good thing, contrary to what often happens in more traditional educational settings.

Education specialists are talking about this type of teaching and many experts attribute it benefits to the cognitive, social and physical development of children. Many teachers have also become interested in such nature-based teaching methodologies. María Mayorga trains them so that they can adapt their curricular knowledge, explaining in this RTVE report how materials from nature can be adapted to the different curricular contents children have to learn: for example, a domino made of stones to introduce mathematical concepts and colours or storytelling sticks for oral narration or reading and writing.

Learning to add with strawberries, finding the points of the compass from the moss on a tree trunk and learning to ask ourselves questions. Taking education out of the classroom to put it into perspective.

With these three experiences we have tried to bring the educational meaning of “personalisation” to ground level, going beyond the learning processes from Intelligent tutoring systems, so much in vogue nowadays. Thus, the broad vision of pedagogical “re-adaptation or personalisation” will have to be in line with UNESCO’s understanding of educational quality which, as we have explained in other posts, one with a prevailing concept of belonging. This is usually defined as “the need for education to be meaningful for people from different social strata and cultures and different abilities and interests so that they can take the contents of global and local culture as their own, and establish themselves as proper subjects, developing their autonomy, self-governance and their own identity”.

It is for this reason that the experiences presented here speak of a flexible education adapted to the needs and characteristics of students from a wide range of social and cultural contexts. These three approaches therefore move from a homogeneous pedagogy to one of diversity, continuously generating opportunities for their students to enrich them through teaching and learning processes in the classroom, optimising their personal and social development.